Non-native species used in mine reclamation: Benefits and risks

Tailings reclamation is a critical process that involves restoring land upon completion of the mining process and best started early in the mine operation. Historically, hardy vegetative species were selected on their merit to thrive in difficult conditions and help stabilize the surface. However, some of these hardy plants have later become invasive species, causing ecological and economic harm. In this article, we will discuss the utilization of several hardy vegetation species that have become invasive species and the importance of selecting appropriate natural vegetation for land reclamation.

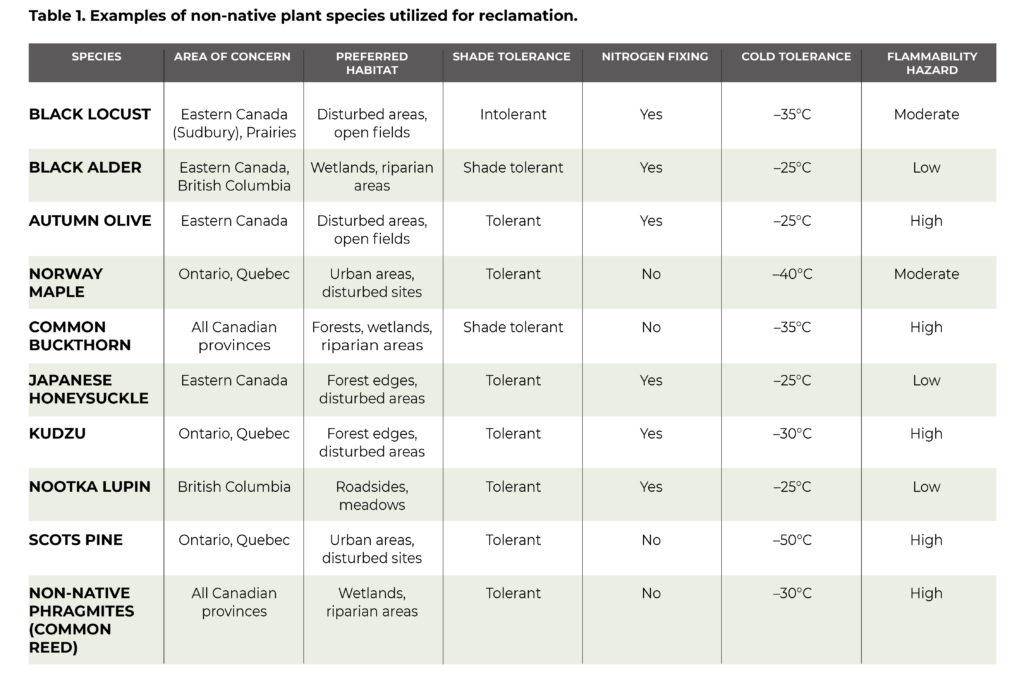

Autumn Olive is a species that was once used extensively for erosion control, especially in western North America. This species is native to Asia but was introduced to North America in the 1830s. It has since spread rapidly and is now considered an invasive species in several regions, including Ontario. Autumn olive can grow in poor soil conditions and produce abundant fruit, which birds and other animals can spread. Although it can be difficult to control, measures such as late season cutting and spraying have proven effective.

Black Locust is another hardy plant that has become an invasive species. This species was utilized to regenerate the Vale tailings area in Ontario because it grows incredibly fast on tailings, and the wood is incredibly durable and highly prized. However, it is also incredibly invasive and can outcompete native species, reducing biodiversity. Black locust can be controlled through mechanical means, such as cutting or burning, or through the use of herbicides.

Black Alder is a species that was brought from Europe and is an Ontario invasive species. It was originally used for erosion control at mine sites but has since spread to other areas. Black alder can tolerate wet and acidic soils, making it an ideal species for land reclamation. However, it can also spread rapidly and outcompete native species, reducing biodiversity. Control measures for Black alder include cutting or pulling the plants and preventing seed production.

Scots Pine is a species that is often seen on entrances to older mine sites and was once champion to restore abandoned farmland in central Ontario. Scots pine can easily outcompete other conifers.

Norway Maple is not necessarily planted in mining locations but was extensively previously used in Toronto to replace dead elm trees. Norway maple is a popular ornamental tree that can grow in a wide range of soil and climate conditions. However, it is also invasive and can outcompete native species, reducing biodiversity. Control measures for Norway maple include cutting or girdling the tree and using herbicides.

Japanese Honeysuckle is another species that has become invasive. It was introduced and advocated by the United States Soil Conservation Service as the best action to prevent erosion. However, it can spread rapidly and outcompete native species, reducing biodiversity. Control measures for Japanese honeysuckle include cutting or pulling the plants and preventing seed production.

Nootka Lupin is a species that is common in western North America and was brought to certain areas in northern Europe for erosion control. It became incredibly invasive in these areas, reducing biodiversity. Certain annual lupins have the ability to uptake arsenic in the root system and have been studied as an option for bioremediation. Nootka lupin is commonly controlled by pulling the plant.

Non-native Phragmites is perhaps one of the fastest spreading invasive grasses observed in Canada. The tall reed-like grasses thrive in wetlands and drastically reduce biodiversity in ecologically sensitive areas.

These grasses were originally examined for their ability to bioaccumulate heavy metals on tailings areas – but thankfully the concept was not implemented by the mining industry.

Awareness is key to preventing the introduction and spread of invasive species. It is important for mine reclamation specialists and government staff to research and choose appropriate plant species for their specific needs in a comprehensive risk assessment. They should also be aware of the potential risks of introducing non-native species and take steps to prevent their spread, which includes future monitoring of plant populations.

However, it is important to note that not all non-native species are invasive and harmful. Some have been successfully introduced and are now an integral part of many ecosystems. The key is to carefully assess the potential risks and benefits of introducing a species before doing so and to monitor its impact over time.

In conclusion, the use of non-native species for land reclamation has been both beneficial and detrimental. If possible, utilize native plant species for reclamation. While these plants were once chosen for their ability to thrive in harsh environments and provide important ecological benefits, many have since become invasive and harmful to native ecosystems.

Steve Skjonsby is a freelance writer.

Comments